I used to write down numbers.

Well, for a few weeks in fourth grade, I wrote down numbers until I grew tired of it. On a sheet of ordinary paper I simply wrote one number after another and kept going.

… 2371 2372 2373 2374 2375 2376 2377 2378 2379 2380 2381 2382 …

You get the idea. WHY THE HECK DID YOU DO THIS, I hear you cry. As Tevye once said, “I will tell you. I don’t know.” I remember classmates leaning over to watch me to this, especially when an interesting number was coming up, like 4444. Fourth grade must not have been that exciting if David’s numbers were the best show in the room.

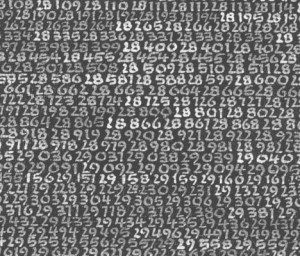

This whole episode flashed back into my memory this week when I read an obituary of painter Roman Opalka, who died on August 6th at age 79. Opalka wrote down numbers, only he kept at it for the rest of his life. He called each of his paintings a “detail,” and they all had the same title: “Opalka 1965 / 1-∞”. Each detail was the same size as his studio door in Warsaw, and the numbers on each detail picked up where the previous one had ended. As he painted each number, he whispered its name in his native Polish. He started the project in 1965, and painted about 400 numbers each day. By the time he died he was well over 5 500 000—he used no commas—though he had originally hoped to reach 7 777 777.

At first he painted white numbers on a black background, but in 1968 he changed to grey, and in 1972 he began adding 1% more white to the grey background each year. By the 2008 the ground was essentially as white as the figures: both the numbers and the visibility merging into infinity.